Unaviodable Yet Unneccesary

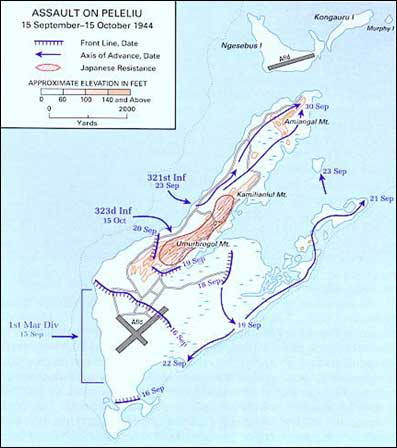

Only two minutes off schedule, on 15 September 1944, the first troops began landing at 0832, with the 1st Marines on the far left, 5th Marines in the middle, and 7th Marines on the right (southern) end of the beaches.11 The regiments on the flanks were to move inland and wheel outward, while the 5th Marines was to push across the airfield to the eastern side of the island. Should this be accomplished as planned, the entire southern end of the island – better than half the entire land mass – would be in American hands, and the rest of the operation would be over quickly. Rupertus, apparently brimming with confidence in his men and himself, declared that Peleliu would be taken by the 1st MarDiv in only a few days.

The Japanese, during the Navy's bombardment and Rupertus' blustering, had hunkered down in their caves, bunkers, pillboxes, and trenches, waited out the preliminary fires, and then assumed their well-protected, well-hidden positions. Compared to earlier island assaults, few Japanese were arrayed directly opposite the beaches. Most were just inland, on the flanks of the beaches, and in the steep mountains immediately north of the airfield. COL Nakagama's troops demonstrated a great deal of discipline in not firing wildly at landing craft while they were far out to sea, and in doing so reveal their positions to naval fire. During the 3 day bombardment, they also held their fire for the same reason. Consequently, the vast majority of positions, and virtually all those holding heavy weapons, were unscathed as of D-Day.

For the marines, things did not go according to plan. Despite the seemingly massive naval fires, skilled air support, and their undisputed bravery under fire, the attack soon bogged down. 1st Marines suffered the most, finding themselves facing a 30-foot high coral ridge. Japanese gunners swept the marines' positions on both the northern and southern ends of the beach, and only the 5th Marines, in the middle, made any real progress in the first hours of the assault, reaching the eastern side of the island by 1500 on D-Day; 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines was the first to reach the eastern shore, thus cutting off Japanese defenders to the south.

The Japanese also displayed even more uncharacteristic discipline by not resorting to a drunken banzai attack, or other uncoordinated, wasteful actions. Late in the afternoon a semi-coordinated tank and infantry attack, launched from the north side of the airfield, took place, involving somewhere between 11 and 17(12) tanks and an unknown number of infantrymen. Although more coordinated than the standard frontal charge, the tanks dashed ahead of the unprotected infantry, who were quickly cut down and dispersed. The tanks, meanwhile, were destroyed by marine tanks and anti-tank gunners. Still, before sunset on D-Day, it was quite apparent that 1st MarDiv was facing an enemy that was not playing by the rules established thus far in the Pacific.

Both 1st and 7th Marines experienced punishing enfilade fire, while 5th Marines tried hard to keep contact with its brother regiments as it moved across the airfield. D-Day ended with, overall, little divisional progress, and heavier casualties than expected. MG Rupertus landed on the morning of D+1 to take personal command of the operation, but was hampered early on by poor communications with outlying units; he had no clear picture of the casualties in 1st or 7th Marines, and equally unclear information about their current tactical situations. Additionally, Rupertus had broken his ankle in an earlier training accident, and was thus unable to easily move to his forward units to see the situation personally.

Over the next week, 1st Marines pushed forward, during which time it reached the base of what became known as 'Bloody Nose Ridge,' a large coral ridge line that overlooked the airfield, and on which the Japanese had entrenched numerous mortars and fighting positions. 1st Marines engaged "in some of the most vicious and costly fighting of the entire Pacific campaign"(13) during this 8-day period, suffering almost 50% casualties along the way. On D+2, MG Rupertus, despite the slow going on his division's flanks and the mounting casualties in 1st Marines, informed III Amphibious Corps, in charge of the overall attack in the Palaus, that the situation was well in hand and would, again, be over within days. This gave the green light for the 81st ID to begin its operations on the islands of Anguar and Ulithi, both secondary objectives in the Palau campaign. Although Rupertus had committed his entire division, including his two reserve battalions on D-Day, he insisted that his division alone could, and would, take Peleliu; the marines did not need a fresh army division to help them.

5th and 7th Marines, up to D+8, reached their objectives of securing the airfield and southern portion of the island. A damaged navy torpedo bomber was the first American plane to land, and did so on D+3;(14) thereafter, on 24 September, marine fighter aircraft began landing on Peleliu. Until the marines established their airbase on Peleliu, close and deep air support was provided entirely by carrier-based aircraft under the direction of the navy. Although 1st MarDiv's artillery was landed on D+2, extensive use of land and carrier-based air support was made throughout the battle.

While the marines fought for every inch of ground on Peleliu, the army's 81st ID made relatively quick work of Anguar and Ulithi; in fact, no enemy troops were found on the latter of the two islands, and relatively light casualties were sustained in taking the former. Meanwhile, 1st Marines, under COL Lewis B. 'Chesty' Puller, continued to bleed, and be admonished to keep up the fight by MG Rupertus, still stubbornly clinging to the notion that Peleliu would be secured in only a few more days. When MG Roy Geiger, III Amphibious Corps Commander, went ashore on 21 September to get a first-hand look at the invasion, he was dismayed by the lack of progress and high casualty count. He asked MG Rupertus if he needed support, in the form of army units now wrapping up their operations on Anguar, but Rupertus demurred. After what has been reported as a heated discussion,(15) Geiger informed Rupertus that one regimental combat team (RCT) of the 81st ID would be joining 1st MarDiv as soon as possible. The 321st RCT would land on Peleliu on 23 September and "relieve Puller's remnants."(16)

During the next week of fighting, the marines and army together reached the northern end of the island and made a small, successful amphibious assault on the islet of Ngesebus, where there was an enemy airfield still under construction. In reaching and securing northern Peleliu, American forces accomplished two vital goals. First, they cut off the Japanese garrison on Peleliu from any hope of seaborne reinforcement or resupply from the northern islands of Koror and Babelthuap. Second, they succeeded in completely surrounding the rugged Umurbrogol Mountains, where the last Japanese defenders were entrenched. The Japanese on those northern islands did attempt to reinforce Nakagama's command, twice sending barges down from Koror; although about 600 additional troops did reach Peleliu, they did so without most of their equipment, their small convoy having fallen victim to American air attacks.

The Umurbrogols now surrounded, the remaining Japanese under COL Nakagawa put up an increasingly stout defense, forcing the Americans to fight for every inch of rough terrain. Flamethrowers, mounted on LVT(4)s and man-portable, were essential to American progress, as were various small demolition charges. The fighting took place in such a small area that marine aircraft, flying from Peleliu's airfield, did not even have time to retract their landing gear before dropping their bombs on the nearby mountains. The fighting on the ground continued, with COL Nakagawa's troops using, to great effect, their massive 150mm mortars(17) and their extensive cave networks.

Throughout this period, Rupertus continued to insist that his marines would secure the island shortly. Like the Japanese throughout the Pacific, however, the enemy on Peleliu fought only harder as their situation became more dire. By early October the pocket of resistance in the Umurbrogol range was reduced to an area of some 900 by 400 yards; the rest of the island was already firmly in American hands. Thus far, American forces had suffered almost 900 killed and 4500 wounded or missing; "of [the] total of 5388 casualties, 5044 were members of the First Marine Division."(18) Despite these massive numbers, and the fact that fighting was still going on in the mountains, on 12 October MG Geiger declared the island itself secured. The battered 1st MarDiv was ordered from the line, to be replaced entirely by elements of the 81st ID. By the third week of October the majority of marines were gone, save for some support troops; the army was left the job of reducing the pocket of defenders in the mountains.

81st ID would employ siege tactics against the last Japanese, completely surrounding and constantly pummeling their defenses with massive air and artillery fires, dangling satchel charges in front of cave openings on cliffs, and eventually using armored bulldozers to collapse cave openings. It would take another 6 weeks, until the end of November, before consistent, organized resistance was ended, and Japanese stragglers were found on the island for years afterward. All told, the Japanese lost about 11,000 men on Peleliu, with only 202 captured throughout the battle; only 19 of these were Japanese, the others being Korean and Okinawan laborers. American forces suffered just over 1500 killed and some 6700 wounded or missing.(19) Regardless, the operational objectives in the Palaus had been reached: Peleliu and its airfield were in American hands, the smaller island of Anguar, also home to an airstrip, had also been seized, and a fleet-sized anchorage had been taken at Ulithi. These accomplishments are clear, and beyond dispute; the means by which they were reached, and the utility of them once seized, however, are.

Written by Jeremy Gypton - Copyright © 2004 Jeremy Gypton

http://www.militaryhistoryonline.com/wwii/peleliu/bloody.aspx